| |

|

Typography is the art and technique of arranging type, type design, and modifying type glyphs. Type glyphs are created and modified using a variety of illustration techniques. The arrangement of type involves the selection of typefaces, point size, line length, leading (line spacing), adjusting the spaces between groups of letters (tracking) and adjusting the space between pairs of letters (kerning). |

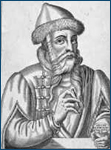

Around 1450, Johannes Gutenberg introduced what is generally regarded as an independent invention of movable type in Europe, along with innovations in casting the type based on a matrix and hand mould. Gutenberg was the first to create his type pieces from an alloy of lead, tin and antimony-the same components still used today. |

Typography is performed by typesetters, compositors, typographers, graphic designers, art directors, comic book artists, and clerical workers. Until the Digital Age, typography was a specialized occupation. Digitization opened up typography to new generations of visual designers and lay users. |

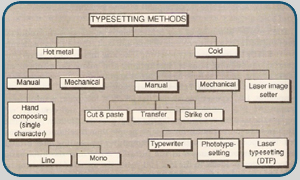

Typesetting involves the presentation of textual material in graphic form on paper or some other medium. Before the advent of desktop publishing, typesetting of printed material was produced in print shops by compositors or typesetters working by hand, and later with machines. |

The general principle of typesetting remains the same: the composition of glyphs into lines to form body matter, headings, captions and other pieces of text to make up a page image, and the printing or transfer of the page image onto paper and other media. The two disciplines are closely related. For example, in letterpress printing, ink spreads under the pressure of the press, and typesetters take this dynamic factor into account to achieve clean and legible results. |

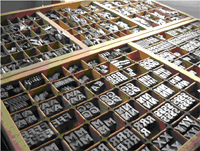

During the letterpress era, moveable type was composited by hand for each page. Cast metal sorts were composited into words and lines of text and tightly bound together to make up a page image called a forme, with all letter faces exactly the same height to form an even surface of type. The forme was mounted in a press, inked, and an impression made on paper. |

| Hand compositing was rendered obsolete by continuous casting or hot-metal typesetting machines such as the Linotype machine and Monotype at the end of the 19th century. The Linotype, invented by Ottmar Mergenthaler, enabled one machine operator to do the work of ten hand compositors. Later advances such as the typewriter and computer would push the state of the art even farther ahead. Still, hand-compositing and letterpress printing did not fall completely out of use, and since the introduction of digital typesetting, it has seen a revival as an artisanal pursuit. However, it is a very small niche within the larger typesetting market. |

Phototypesetting |

|

Phototypesetting systems first appeared in the early 1960s and rapidly displaced continuous casting machines. These devices consisted of glass disks (one per font) that spun in front of a light source which selectively exposed characters onto light-sensitive paper. Originally they were driven by pre-punched paper tapes. Later they were hooked up to computer front ends. |

One of the earliest electronic photocomposition systems was introduced by Fairchild Semiconductor. The typesetter typed a line of text on a Fairchild keyboard that had no display. To verify correct content of the line it was typed a second time. If the two lines were identical a bell rang and the machine produced a punched paper tape corresponding to the text. With the completion of a block of lines the typesetter fed the corresponding paper tapes into a phototypesetting device which mechanically set type outlines printed on glass sheets into place for exposure onto a negative film. Photosensitive paper was exposed to light through the negative film, resulting in a column of black type on white paper, or a galley. The galley was then cut up and used to create a mechanical drawing or paste up of a whole page. A large film negative of the page is shot and used to make a plates for offset printing. |

Digital Era |

The next generation of phototypesetting machines to emerge were those that generated characters on a Cathode ray tube. Typical of the type were the Auto logic APS5, III Video Comp and Linton 202. These machines were the mainstay of phototypesetting for much of the 1970s and 1980s. Such machines could be 'driven online' by a computer front-end system or take their data from magnetic tape. Type fonts were stored digitally on conventional magnetic disk drives.

Computers excel at automatically typesetting documents. Character-by-character computer-aided phototypesetting was in turn rapidly rendered obsolete in the 1980s by fully digital systems employing a raster image processor to render an entire page to a single high-resolution digital image, now known as image setting. |

The first commercially successful laser image setter, able to make use of a raster image processor was the Monotype Laser comp. ECRM, Comp graphic (later purchased by Agfa) and others rapidly followed suit with machines of their own. |

The minicomputer systems output columns of text on film for paste-up and eventually produced entire pages and signatures of 4, 8, 16 or more pages using imposition software on devices such as the Israeli-made Scitex Doles. The data stream used by these systems to drive page layout on printers and image setters led to the development of printer control languages such as Adobe Systems PostScript and Hewlett-Packard's HP PCL. |

Before the 1980s, practically all typesetting for publishers and advertisers was performed by specialist typesetting companies. These companies performed keyboarding, editing and production of paper or film output, and formed a large component of the graphic arts industry. In the United States these companies were located in rural Pennsylvania, New England or the Midwest where labor was cheap, but within a few hours' travel time of the major publishing centers. |

In 1985, desktop publishing became available, starting with the Apple Macintosh, Adobe PageMaker (and later QuarkXPress) and PostScript. Improvements in software and hardware, and rapidly-lowering costs, popularized desktop publishing and enabled very fine control of typeset results much less expensively than the minicomputer dedicated systems. At the same time, word processing systems such as Wang and WordPerfect revolutionized office documents. They did not, however, have the typographic ability or flexibility required for complicated book layout, graphics, mathematics, or advanced hyphenation and justification rules.

|

By the year 2000 this industry segment had shrunk because publishers were now capable of integrating typesetting and graphic design on their own in-house computers. Many found that the cost of maintaining high standards of typographic design and technical skill made it more economical to out-source to freelancers and graphic design specialists. |

| The availability of cheap, or free, fonts made the conversion to do-it-yourself easier but also opened up a gap between skilled designers and amateurs. The advent of PostScript, supplemented by the PDF file format, provided a universal method of proofing designs and layouts, readable on major computer and operating systems. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|